The New PM before an roaring audience. Source: LCP - Assemblée nationale

Michel Barnier, the new Prime Minister of France, stepped out on Tuesday before the National Assembly to present his plan to fix what everyone knows is a mess: France’s budget. He did not spare the gloom, announcing what is effectively austerity— public spending will be cut, and taxes will go up (at least for a while).

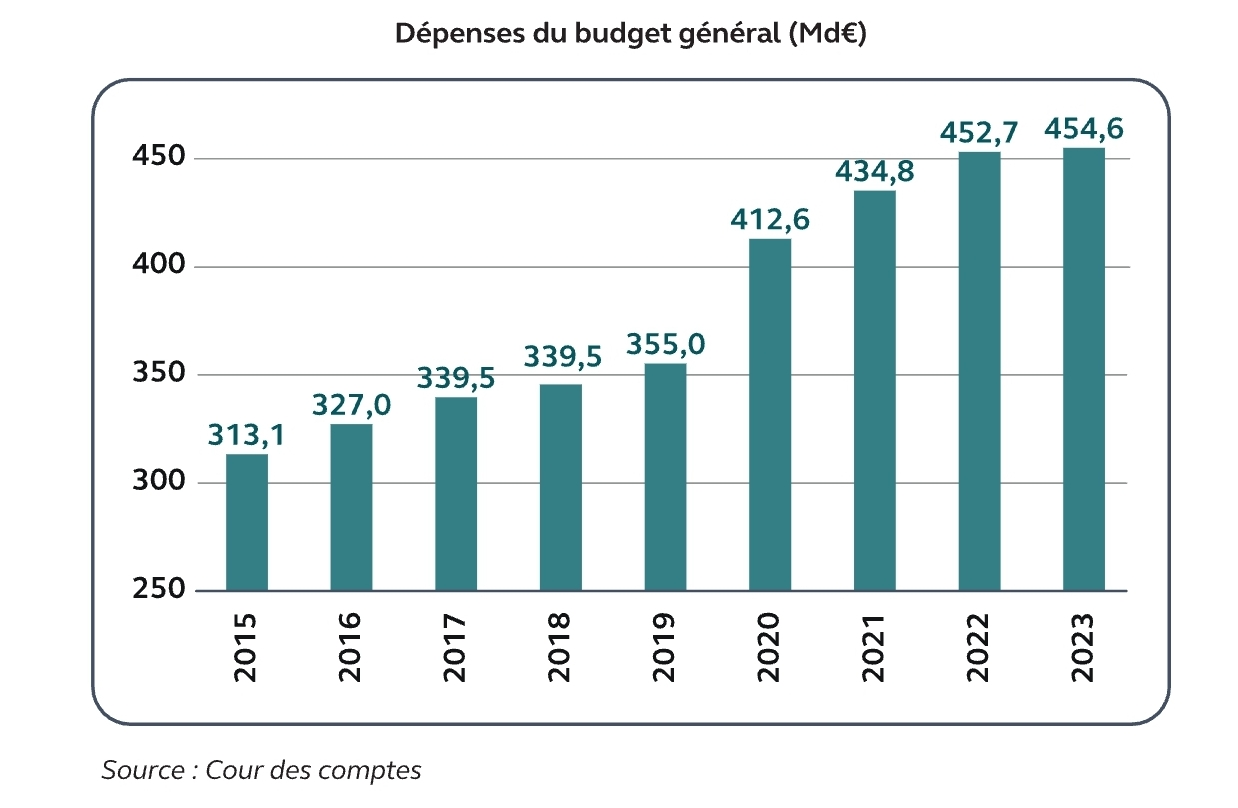

Last year, France’s deficit hit €154 billion, or 5.5% of GDP. It’s high. And Barnier said it could even reach 6% this year. It would just add more to the already enormous €3 trillion of public debt France holds, which is 112% of its GDP.

Barnier pointed to a sword of Damocles hanging over the nation. A dramatic way of saying: we can’t keep living on the credit cards anymore, chérie. 1974, was the last time the French household was not in deficit.

It’s the Pandemic, not me.

What happened really was the Pandemic. In 2019, France’s % of GDP was merely 2.4% of the GDP. When the before the new flu came through, the French State, like many others, spent a wad of money to cushion the economic and social blow of their measures— people needed help, and the economy was sagging.

Post-pandemic, Macron has failed to tighten the belt. France keeps spending. Meanwhile, taxes have been gradually reduced as part of Macron’s efforts to be business-friendly.

The result is an enormous fiscal hole. And it’s up to Barnier now.

Knock Knock, Who’s there? Austerity

Barnier’s plan is simple: reduce the deficit to 5% of GDP by 2025, and then, by 2029, bring it down to the EU’s mandatory 3%. How will he do it? He says that plan is two-thirds spending cuts and one-third tax increase.

Those who claimed to have done the math on it say Barnier means approximately €40 billion in spending cuts and raising taxes to bring in an additional €20 billion next year.

Barnier did not conjure the A word, but the measures he presents sure sound like it. This is most noticeable in the policies of taxation, where everything is made to sound ‘temporary’ or ‘exceptional.’ He wants to pluck the geese, but not have them hissing.

Too much social spending.

The big problem that Barnier blames is France’s excessive social spending. It jumped during Covid-19, and is now too scared to come back down.

At the Bank of France, the Governor, François Villeroy de Galhau, had his two centimes:

The root cause of the "French malaise" is the continuing increase in public expenditure. I am a fervent defender of the European social model – with strong public services and fiscal and social redistribution – but there is no escaping the fact that in France it 'costs' us almost 10 GDP points more than our European neighbours.

Source: Banque de France

When you take the overall result, the French government spends more than 58% of GDP— 8% higher than the eurozone average (Eurostat). With so much money allocated to an enormous social safety net, cutting it without protest is difficult. If you think cutting social spending is tough in your own country, imagine France. They will protest ketchup if they have to.

It’s a delicate position. While Barnier will reduce spending, he must avoid doing so in a way that risks social unrest. However, the situation no longer allows for precise cuts. The deficit is now so large that more drastic measures are needed. A butcher’s knife.

The monster under the bed

This is not an overnight solution. There remains the huge pile of debt that France has carefully stashed under its bed. Every year, just to service this monster, the state is spending almost the same as it is on defence.

Meanwhile, France’s borrowing costs are rising as markets lose confidence in its finances. Recently, French bonds had higher costs than Greece or Spain. Not a point of pride for the French. To them, it’s like losing a race to a guy in sandals.

It’s not without reason either. In May, the S&P Global downgraded the French credit rating. And the EU has put France on the naughty list because its deficit exceeded the 3% of GDP deficit threshold required.

Why? One governor of a eurozone central bank was reported in Le Monde to have said: "France has zero credibility in Europe when it promises to cut spending.”

Good idea that was anonymous.

More tax but not too much

As for taxes, Barnier is tiptoeing. Macron has spent years carefully cultivating France’s business-friendly appearance. So raising taxes— especially on corporations— might find some resistance in the Presidential Palace. But Barnier knows just as well as Macron that tax increases are inevitable. Otherwise, that deficit just ain’t closing.

France already has one of the highest tax burdens in the OECD, collecting way more in taxes as a % of GDP than most of its Euro buddies. But there are already reports that the government plans to raise between €15 billion and €20 billion in new taxes this year.

In a recent interview, Barnier made it clear that he would not increase taxes on the lower and middle classes. Instead, the wealthy and ‘certain large corporations’ will be hit. Much of this he veneered with the moral gravity of “fiscal justice.”

One idea would be a temporary increase in the corporate tax, an idea last floated by the Former Budget Minister Bruno Le Maire. If applied, it would reverse Macron’s headline reduction of the corporate rate from 33.3% to 25%. Another proposal floating about is to end corporate subsidies or impose a tax on share buybacks, which might be able to scrape €200-300 million. You see how daunting Barnier’s task is, now.

But the funny thing to remember about taxes is that once they’re introduced, they tend to stick around. Like a foot fungus. The massive taxes during the First World War, namely the income tax, was announced as a “provisionary” measure. Yet it ended up feeding growing public services, for which the demand only grew. So, it stayed.1

They will be careful with tax. But I warn you that whatever Barnier manages to impose, it will be awfully tempting for the state to keep it there.

The Economy: Mediocre, but some hope.

What looms over the French budget is a tired economy. In the third quarter of 2024, GDP rose by a modest 0.2%, while household purchasing increased by the same amount.

This is reason for that over used euphemism: ‘cautious optimism.’ But really, these results also mark the end of the post-pandemic bounce. After the sudden economic drop in 2019, things jumped up in the following years, reminding us that there is still a heart beating in the French economy.

France GDP Growth Rate. Source.

Still, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic. France remains one of the world’s top destinations for foreign direct investment. The profit margins of non-financial corporations have well recovered from the 2009 recession and continue. Its labour force is highly educated. Meanwhile, the state is strong. People pay their taxes (generally), and the state has many productive assets.

And let’s not forget that the health of the economy matters to the budget. The more people and businesses earn, the more they can be taxed. If the economy falters, Barnier’s fiscal plans become much harder. This is why some are reluctant to whip taxes up too high.

Political obstacles

The immediate challenge for Barnier, though, is not economic— it’s political. Getting the budget passed is not an easy task.

Barnier’s government holds only a relative majority in the National Assembly. He will need the support of either the far-right or the far-left to get anything done. Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right, has just signalled she might be ready to support the budget if Barnier agrees to support stricter immigration laws.

There are mechanisms to push it through regardless (Art 49.3). But it risks bringing down the entire government, if the opposition can pull an absolute majority. Sitting angrily is the left-wing coalition that was just excluded from government. While no friend of the right, they are eager to bring down Barnier’s party if given the chance.

Time is not on Barnier’s side either. Normally, the law regarding finances says that the budget has to be presented to the parliament on the first Tuesday of October. That was two days ago.

There are plenty of measures for them to deal with such a deadlock if it continues. In the worst-case scenario, special decrees can be put in place. This happened in 1963 under the Pompidou government when a budget was not adopted until 23 February.

At least, with the clock ticking, things might move faster. Barnier certainly painted a bleak enough picture to motivate the crowd. If there is a drawn-out battle, it would risk worsening France’s delicate financial situation.

Conclusion

Can Barnier pull this off? We certainly hope so. President Macron is no enemy to the government, and Barnier is well-regarded for his role in the Brexit negotiations for the EU.

The plan is clear enough: cut spending without protests, and raise taxes without killing economic growth. Then France’s budget might just get back on track. Then again, don’t expect a balanced budget. That hasn’t happened since the 1970s.

In other news

What the new French government means for Brussels (Politico EU)

Starmer vows to turn page on UK’s relationship with the EU (The Guardian)

Former Dutch PM Now NATO chief (DW)

Driving on empty: The German government has few options to help an ailing car industry (Politico EU)

I’m aware. It’s not a war.